Precautionary Principle

“The government solution to a problem is usually as bad as the problem”.-Milton Friedman

Source: http://www.nature.com/embor/journal/v8/n4/full/7400947.html

Quotes about the Precautionary Principle:

"The truly fatal flaw of the precautionary principle...is the unsupported presumption that an action aimed at public health protection cannot possibly have negative effects on public health". 14- Frank Cross

“The precautionary principle takes many forms. But in all of them the animating idea is that regulators should take steps to protect against potential harms, even if causal chains are unclear and even if we do not know the harms will come to fruition... [I]n its strongest forms, the precautionary principle is literally incoherent, and for one reason: There are risks on all sides of social situations. It is therefore paralyzing; it forbids the very steps that it requires. Because risks are on all sides, the precautionary principle forbids action, inaction, and everything in between”. 15-Cass Sunstein

"The whole aim of practical politics is to keep the populace alarmed -and hence clamorous to be led to safety -- by menacing it with an endless series of hobgoblins, all of them imaginary." 16-H. L. Mencken

“The environmentalist’s dream is an egalitarian society based on: rejection of economic growth, a smaller population, eating lower on the food chain, consuming a lot less, and sharing a much lower level of resources much more equally.” 17- Aaron Wildavsky

The Precautionary Principle has been described by environmental activists as a common sense way to protect our health and environment. Then again, people have been misled by environmental activist in the past.

Precaution has always had an essential role in regulating any risks. Every risk

involves some uncertainties, which must be bridged by precaution in making any decision to reduce risk. In other words, few if any regulatory decisions could be taken in the absence of some recognition of risk and some precaution to reduce potential risks.

“Too safe for our own good?”-Washington Times

A tactic that has been used by regulatory agencies in the United States in recent years is to use concepts that would certainly be considered precautionary, but not explicitly state in the regulation that this concept is based upon the Precautionary Principle. This differs from Europe and most of the world where it is generally explicitly states that a regulation or treaty is based upon the Precautionary Principle.

Yet, proponents of the Precautionary Principle do not seek merely to make the application of precaution more explicit. They also seek to apply more precaution than has been applied in the past. 18 In fact one could argue that the Precautionary Principle yields a great deal of power to bureaucrats within regulatory agencies with little scientific evidence or cost/benefit analysis to justify its actions. The rationale put for forward by the proponents in that the regulation maximizes protection of the environment or human health or occupational safety with little evidence that the regulations will be effective at achieving more that increasing regulatory burdens on the regulated to the benefit of the regul8fff6dators.

There are two broad classes of definitions of the Precautionary Principle: first the strong version of PP which basically says that take no action unless you are certain that it will do no harm; the second weak version of PP which would state that lack of full certainty in so justification for preventing an action that might be harmful 19. Both definitions are problematic and will be dealt with in later sections.

The Precautionary Principle is a tool that allows the one to apply this principle into situations that involve some element of estimates of risk. In environmental applications, the precautionary principle is offered as an alternative to the traditional risk assessment idea that is typically used by federal and state government to estimate the cause/effect relationship to human, animal or environmental health. Risk assessment can be describes as estimating the hazard of a substance or action in conjunction with an estimate of the likelihood that there will be some exposure to the hazard, resulting in the equation:

Risk=Hazard x Exposure

Proponents of use of the Precautionary Principle as a basis for regulating human activity argue that regulations should be based on worst-case estimates of hazard alone, without regard for how small the risk of an adverse effect might be. Taken to one logical conclusion, the hazards of travelling by car (possibility of a crash) alone would be the basis of regulation rather than risks based on actual measurements of exposure to adverse events (risk = probability of a crash x incidents per mile driven). Arguments for regulations based on precaution have gained little success in areas such as transportation, where the population at large has personal experience with potential risks. In areas where the general population has little understanding or experience, such as science-based regulation intended to protect human health and/or the environment, proponents of the Precautionary Principle have been much more successful.

The Precautionary Principle can be applied in most areas of political policy that deals with risk. One example that has been recently cited is the Obama Administration’s response in the wake of the BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill accident:

Wall Street Journal-The ‘Paralyzing’ Principle June 21, 2010

It has been argued that the Precautionary Principle has crossed over into other risk areas such as defense policy.

The Terrible ‘Ifs’

In 2001, The New York Times named The Precautionary Principle one of the year’s top ideas.

Reject the Precautionary Principle, a Threat to Technological Progress-From Liberate to Stimulate: A Bipartisan Agenda to Restore Limited Government and Revive America's Economy -Greg Conko

http://cei.org/agenda-congress/reject-precautionary-principle-threat-technological-progress-0

Are Risk Assessment And The Precautionary Principle Equivalent? -Andrew Apel

http://cei.org/outreach-regulatory-comments-and-testimony/are-risk-assessment-and-precautionary-principle-equivale-0

The first effort to bring the precautionary principle to the United States was at the Wingspead Conference on the Precautionary Principle in January 1998. The conference brought together environmental activists to discuss implementing the precautionary principle and barriers to implementation.

At that conference, the following statement was formulated:

The Wingspread Consensus Statement on the Precautionary Principle:

“The release and use of toxic substances, the exploitation of resources, and physical alterations of the environment have had substantial unintended consequences affecting human health and the environment. Some of these concerns are high rates of learning deficiencies, asthma, cancer, birth defects and species extinctions; along with global climate change, stratospheric ozone depletion and worldwide contamination with toxic substances and nuclear materials.

We believe existing environmental regulations and other decisions, particularly those based on risk assessment, have failed to protect adequately human health and the environment - the larger system of which humans are but a part.

We believe there is compelling evidence that damage to humans and the worldwide environment is of such magnitude and seriousness that new principles for conducting human activities are necessary.

While we realize that human activities may involve hazards, people must proceed more carefully than has been the case in recent history. Corporations, government entities, organizations, communities, scientists and other individuals must adopt a precautionary approach to all human endeavors.

Therefore, it is necessary to implement the Precautionary Principle: When an activity raises threats of harm to human health or the environment, precautionary measures should be taken even if some cause and effect relationships are not fully established scientifically.

In this context the proponent of an activity, rather than the public, should bear the burden of proof.

The process of applying the Precautionary Principle must be open, informed and democratic and must include potentially affected parties. It must also involve an examination of the full range of alternatives, including no action”.

Conference Partners

The Wingspread Conference on the Precautionary Principle was convened by the Science and Environmental Health Network, an organization that links science with the public interest, and by the Johnson Foundation, the W. Alton Jones Foundation, the C.S. Fund and the Lowell Center for Sustainable Production at the University of Massachusetts-Lowell.

Wingspread Participants:

| Dr. Nicholas Ashford |

M.I.T. |

Katherine Barrett |

Univ. of British Columbia |

Anita Bernstein |

Chicago-Kent College of Law |

Dr. Robert Costanza |

Univ. of Maryland |

Pat Costner |

Greenpeace |

Dr. Carl Cranor |

Univ. of California, Riverside |

Dr. Peter deFur |

Virginia Commonwealth Univ. |

Gordon Durnil |

Attorney |

Dr. Kenneth Geiser |

Toxics Use Reduction Inst., Univ. of Mass., Lowell |

Dr. Andrew Jordan |

Centre for Social and Economic Research on the Global Environment, Univ. Of East Anglia |

Andrew King |

United Steelworkers of America, Canadian Office |

Dr. Frederick Kirschenmann |

Farmer |

Stephen Lester |

Center for Health, Environment and Justice |

Sue Maret |

Union Inst. |

Dr. Michael M'Gonigle |

Univ. of Victoria, British Columbia |

Dr. Peter Montague |

Environmental Research Foundation |

Dr. John Peterson Myers |

W. Alton Jones Foundation |

Dr. Mary O'Brien |

Environmental Consultant |

Dr. David Ozonoff |

Boston Univ. |

Carolyn Raffensperger |

Science and Environmental Health Network |

Dr. Philip Regal |

Univ. of Minnesota |

Hon. Pamela Resor |

Massachusetts House of Representatives |

Florence Robinson |

Louisiana Environmental Network |

Dr. Ted Schettler |

Physicians for Social Responsibility |

Ted Smith |

Silicon Valley Toxics Coalition |

Dr. Klaus-Richard Sperling |

Alfred-Wegener- Institut, Hamburg |

Dr. Sandra Steingraber |

Author |

Diane Takvorian |

Environmental Health Coalition |

Joel Tickner |

Univ. of Mass., Lowell |

Dr. Konrad von Moltke |

Dartmouth College |

Dr. Bo Wahlstrom |

KEMI (National Chemical Inspectorate), Sweden |

Jackie Warledo |

Indigenous Environmental Network |

Note the lack of diversity in the participants of the Wingspread delegates. One author remarked “If I hand-picked my delegates, I can achieve consensus on just about anything” 20.

Why proponents (environmental activists) of the Precautionary Principle think this is necessary?

Proponents of the principle claim that there are several reasons why the principle is needed now. These reasons are taken directly from the SEHN website.

-Assimilative Capacity: The notion expressed by Thomas Malthus that population will grow at a faster rate than the rate of growth of resources to support the growing population.

-Changes in human heath patterns: Proponents claim that cancer rates are increasing at an astronomical rate (The proponents’ claims are false). The proponents claim that this increase in cancer rates is due to pesticides, man-made chemicals, and other environmental available chemicals.

-Scientific evidence, scientific uncertainty: The claimed changes in health patterns (which are actually false) are used as evidence of a direct link between environmental factors and adverse health effects. Furthermore, they claim that these effects can seldom be linked decisively to a single factor. Scientific standards for certainty about causation and effect are high. This notion alone is an important factor since it shows that they believe that environmental pollution is one of the most important reasons for these changing health patterns (Environmental activists continue to blame for their “perceived” increase in cancer rates based upon environmental factors where this is actually not the case. The top three risk factors of cancer are smoking, diet/obesity and infection. Certain researchers used the term “environmental” to include the top three risk factors where as other researchers used the term environmental to strictly mean air and water pollution.

The Wingspread noting that little or no evidence of causation is necessary in important in advancing the Precautionary Principle because scientific data are not always supportive of links between environmental pollution and purported changes in health patterns.

-Environmental policies have failed: Proponents believe that we need the Precautionary Principle believe that part of the problem is that the magnitude of the problem is now only becoming evident. PP proponents believe that environmental policies to date have been reactive and the Precautionary Principle would be proactive.

-Quantitative Risk Assessment: According to “Precautionary Tools for Reshaping Environmental Policy”; quantitative risk assessment, which became standard practice in the United States in the mid-1980s and was institutionalized in the global trade agreements of the 1990s, turned out to be more useful in “proving” that a product or technology was not inordinately dangerous 21”. Another way to look at this would be that environmentalist did not care for the results of risk assessments if they proved a product was not harmful.

Components of the Wingspread Consensus on the Precautionary Principle

The Wingspread consensus identifies ten basic precautionary procedures to be considered:

1) Asserting the public trust role in government. Acknowledge role in government touphold, enforce, and enact responsibility for public and environmental health. This also helps establish a long time frame.

2) Valuing environmental health-protecting human and environmental health for the common good.

-Putting values up front

-Giving priority to the Public Good

-Included in the section “burden shifting”

-“Problem” of Narrow Precaution-Argues that in the EU that the focus is first on economics and then on health issues. Wingspan proponents argue that the roles should be reversed (health and then economics). An example of this is the EU’s REACH program.

3) Settling goals- Industry to establish setting its own environmental goals and the use of Green Scorecards

4) Heeding early warning-including:

-Premarket safety testing and review

-Monitoring and tracking

5) Defining harm- Proponents of the principle believe:

-Under Precautionary Policy, all change is not bad

-Focus on serious, irreversible, cumulative or easily avoidable harm

-Precautionary Policy should be used to address serious hazards (or potential harm) and try to find better alternatives

-Includes harm which proponents claim have not been discovered yet such as long-term, delayed responses; cumulative harm from multiple, diverse impacts; cultural and social harm; subtle harms such as endocrine disruption; small changes that trigger larger changes, including ecosystem collapse; and indirect “ripple” effects.

6) Analyzing uncertainty- Precautionary proponents state that due to the complexity of biological systems, scientific proof is beyond the reach of many scientific investigations and observations. Environmental activists believe that policy makers using risk assessment systems that are often misused to create false certainties or the illusion of scientific certainly where none exists.

7) Assessing alternatives- including:

-Environmental impact statements (EIS) (required in the US since 1970 as part of the National Environmental Policy Act)

-Environmentally Preferable Purchasing (established in the US as a voluntary program through the Pollution Prevention Act of 1990)

8) Practicing transparency-including:

-Right to know laws (established in the US since 1986)

-labeling requirements (required in the US and all developed countries for decades)

-The Toxic Release Inventory (TRI) (established in the US since 1986)

-Labeling requirements similar to California’s Prop 65(these are the ubiquitous warning signs in California that, for example, lets beachgoers know that the sand on the beach is “known to the State of California to cause cancer.”)

-Identifying imports that contain Genetically Modified Organisms (GMO) (this was a concern among some Europeans in the 1990s. Cynics observed that the government-promoted GMO hysteria was an effective tool for keeping competition out of European countries.)

9) Practicing democracy- Precautionary Principle proponents believe that in the United States, democracy is not only “thin” but also not fully representative because it excludes large segments of the population: children, prisoners, illegal aliens, and non-voting individuals. They claim that when “victims” are unidentified, full health protection (human health and environment) are rarely achieved.

-Public participation in environmental decisions can lead to better results because:

-non-experts frame problems in a broader manner and not constrained by discipline

-public participation can bring a broader range of expertise and experience into decision making

-Public participation can expose limitation in “expert models”

-Lay judgments reflect sensitivity to values and common sense

-Members of the public are more likely than experts to identify alternatives and solutions and to accommodate uncertainly and consider potential errors in decisions.

10) Shifting burdens

-Compensation and liability for harm

-Performance bonding or insurance requirements

-Ecological taxes

-Cradle to grave producer responsibility 22

Methods of Precaution-Tools used by proponents of the Precautionary Principle (environmental activist)

Source: http://www.newspeakdictionary.com/go-movie.html

■Tools of restriction-including:

-Bans or phase-outs

-Voluntary prevention and Environmental Management Programs

-Caution warnings

-Use restrictions

-Establishing lists of potential harm (red flag lists)

-Lowering exposure or extraction limits

-Temporary restrictions pending further testing

-Action against a class of substances

■Clean production and pollution prevention-which include the following:

-Green Chemistry and Engineering, Clean Science

-Green Design, Ethical Technology (see Sustainablility)

-Biomimicry-Using nature as a guide. Proponents believe that nature is benign.

■Alternative assessments

■Health-based occupational exposure limits

■Reverse onus chemical listing

■Organic agriculture

■Ecosystem management-such as:

-Green social systems such as community supported agriculture

-Adaptive management such as Precautionary learning

-Ecological Medicine: a field of inquire and action seeking to reconcile the care and health of populations, individuals, communities and ecosystems. An approach were scientist and non-scientist take an ecological approach to human health and healing.

■Premarket or pre-activity testing requirements 23

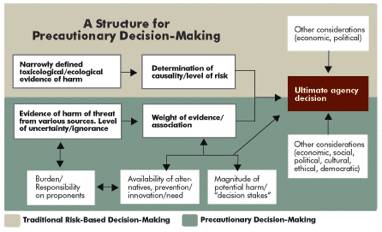

Process Flow of a typical Precautionary Principle situation as defined by environmental activist

This sample process flow was taken from the SEHN document “The Precautionary Principle in Action”. 23 This decision tree provides a consistent basis for advocates to define, examine, and identify alternatives to threats to health and the environment. Following these common-sense, rational steps in the decision-making process, some of which are described in business textbooks, leaves activists less open to charges of emotionalism. Instead of taking a simple opposition stance, advocates can lead a community toward rational and wise solutions.

The steps are simple: first characterize and understand the problem or potential threat; understand what is known and not known; identify alternatives to the activity or product; determine a course of action, and monitor. (If the impacts of a particular activity are known, then the actions taken are no longer precautionary; they are either preventive or control actions.)

Step One: Identify the possible threat and characterize the problem.

The purpose of this step is to gain a better understanding of what might happen should the activity continue and to ensure that you are asking the right questions about this activity. Poor solutions are often a result of badly defined problems. Identify both the immediate problem and any other global issues that might go along with this threat. Here are questions to ask:

Why is this a problem? Presumably it has the potential to threaten public health or the environment.

What is the potential spatial scale of the threat - local, statewide, regional, national, global?

What is the full range of potential impacts? To human health, ecosystems, or both? Will there be impacts to specific species or loss of biodiversity? Are the impacts to waterways, air, or soil? Do indirect impacts need to be considered (such as a product's lifecycle-production and disposal)?

Will some populations (human or ecosystems) be disproportionately affected?

What is the magnitude of possible impacts (intensity)? Is the extent of harm negligible, minimal, moderate, considerable, and catastrophic?

What is the temporal scale of the threat? There are two issues to consider: 1) The time lapse between a threat and possible harm (immediate, near future, future, future generations). The further in the future harm might occur, the less likely that impacts can be predicted, the harder it will be to identify and halt a problem, and the more likely that future generations will be impacted. 2) Persistence of impacts (immediate, short term, mid-term, long-term, inter-generational).

How reversible is the threat? If the threat were to occur would it be easy to fix or last for generations? (easily/quickly reversed, difficult/expensive to reverse, irreversible, unknown)

A note about existing problems: Defining a problem at hand is less difficult than projecting problems from a future project. But the first questions are similar: Is the problem local pollution from a particular facility or broader lack of attention to pollution prevention or both? Is it caused by a government failure or a company's negligence? Is it a serious threat or just an eyesore?

Step Two: Identify what is known and what is not known about the threat.

The goal of this step is to gain a better picture of the uncertainty involved in understanding this threat. Scientists often focus on the what we know, but it is equally, and perhaps more, important to be clear about what we don't know. There are degrees and types of uncertainty, as the later discussion explains. Relevant questions:

Can the uncertainty be reduced by more study or data? If so, and if the threat is not great, a project with substantial benefits might be continued.

Are we dealing with something that is unknowable or about which we are totally ignorant? High uncertainty about possible harm is good reason not to go ahead with a project.

What is known about additive and synergistic effects from exposure to multiple stressors and cumulative effects from combined exposures to various stressors?

Do industry and government claim that an activity is safe mean only that it has not yet been proven dangerous?

You might want to make a chart listing what is known and what is not known about the threat to gain a better comparative picture and understand gaps in understanding.

Step Three: Reframe the problem to describe what needs to be done

The goal of this step is to better understand what purpose the proposed activity serves. For example, a development provides housing, a solvent provides degreasing, a pesticide provides pest management, a factory provides jobs and a product for a specific service.

The problem can then be reframed in terms of what needs to be achieved in order to more readily identify alternatives.

Step Four: Assess alternatives.

Proposed and existing activities are addressed somewhat differently in this step.

Proposed activities: Integral to the precautionary principle is a comprehensive, systematic analysis of alternatives to threatening activities. This refocuses the questions to be considered by a regulator or company from how much risk is acceptable to whether there is a safer and cleaner way to undertake this activity. Assessing alternatives drives ingenuity and innovation. It is more difficult to dismiss proposals that not only name problems but set forth alternatives, or demand that they be considered. The "no action" alternative must be considered: perhaps an activity should not proceed because it poses too much of a threat and/or is not needed.

Existing activities: At this point you would develop and assess a range of alternative courses of action to deal with the problem. The options can be to study further, to completely stop the activity, prevent, control, mitigate, or remediate.

In either case, the assessment of alternatives is a multi-stage process.

First, you might brainstorm a wide range of alternatives, and then screen out those options that seem impossible.

The next stage is to assess the alternatives to determine whether they are politically, technically, and economically feasible. Do not let conventional wisdom limit this assessment. Keep in mind that something that is not economically or technically feasible today may be feasible in the near future. And government agencies and firms rarely consider the "external" costs of threatening activities harm to health, loss of species, etc. which are often unquantifiable. These concerns must be incorporated in the assessment.

The last step of the alternatives assessment is to consider potential unintended consequences of the proposed alternatives. A common criticism of the precautionary principle is that its implementation will lead to more hazardous activities. This need not be true: alternatives to a threatening activity must be equally well examined.

Step Five: Determine the course of action.

Take all the information collected thus far and determine how much precaution should be taken in stopping the activity, demanding alternatives, or demanding modifications to reduce potential impacts. A useful way to do this is by convening a group of people to weigh the evidence, considering the information on the range and magnitude impacts, uncertainties, and alternatives coming from various sources. The weight of evidence would lead to a determination of the correct course of action.

Step Six: Monitor and follow up

No matter what action is taken, it is critical to monitor that activity over time to identify expected and unexpected results. Those undertaking the activity should bear the financial responsibility for such monitoring, but when possible this should be conducted by an independent source. The information gathered might warrant additional or different courses of action.

Source: http://www.sustainableproduction.org/precaution/back.brie.putt.html

Answering the Critics of the Precautionary Principle-Environmental activist coach other activists on the answers by critics of the principle

The SEHN has put out two documents that you can find on their website regarding how to answer the questions of the critics of the Precautionary Principle. According to SEHN “The precautionary principle is a new way of thinking about environmental and public health protection and long-term sustainability. It challenges us to make fundamental changes in the way we permit and restrict hazards. Some of these challenges will pose large threats to government agencies and polluters and are likely to lead to powerful resistance. It is important to anticipate critics of precaution and to know how to respond to their comments” 23. Below are some of the SEHN’s answers for the critics.

Q: The precautionary principle is not based on sound science.

A: Sound science is a matter of definition. Conventional understanding of "sound science" emphasizes risk assessment and cost-benefit analysis. These are value-laden approaches, requiring numerous assumptions about how hazards occur, how people are exposed to them, and society's willingness to tolerate hazard. In fact, because of great uncertainties about cause and effect, all decisions about human health and the environment are value-laden and political.

The precautionary principle recognizes this, and proposes a shift in the basis for making these decisions. Precaution is based on the principle that we should not expose humans and the environment to hazards if it is unnecessary to do so.

Precaution is more thorough than risk assessment because it exposes uncertainty and admits the limitations of science. This is a "sounder" kind of science. Precaution does not call for less science, but more, to better understand how human activities affect our health and environment. But the need for better understanding must not prevent immediate action to protect ourselves and future generations.

Q: This is emotional and irrational.

A: Because we are human, thinking about babies born with toxic substances in their bodies tugs at our emotions. Caring about future generations is an emotional impulse. But these emotions are not irrational; they are the basis for our survival. Precaution is a principle of justice that no one should have to live with fear of harm to their health and environment. Decision-making about health is not value-neutral. It is political, emotional, and rational. Not taking precautions seems irrational.

Q: We will go bankrupt. This will cost too much.

A: There is more reason to believe that precaution will increase prosperity in the long run, through improved health and cleaner industrial processes and products. The skyrocketing costs of environmental damage, health care from pollution, and pollution control and remediation are rarely included in estimates undertaken when precautionary action is advocated. Despite initial outcries about precautionary demands, industry has been able to learn and innovate to avoid hazards. In the area of pollution prevention, thousands of companies have saved millions of dollars by exercising precaution early, before proof of harm. These companies and governments that act similarly become leaders in their field when firmer proof of harm comes along. In taking precaution, however, we should also plan ahead to mitigate immediate adverse economic impacts. Transition planning pulls together different sectors of society to ensure that precautionary action has as few adverse side-effects as possible. Precaution is practiced by setting societal goals, such as that children be born without toxic substances in their bodies, and then determining how best to achieve that goal.

Q: What do you want to do, ban all chemicals? This will halt development and send us back to the Stone Age!

A: Precaution does not take the form of categorical denials and bans. It does redefine development not only to include economic well-being but also ecological well-being, freedom from disease and other hazards.

The idea of precaution is to progress more carefully than we have done before. It would encourage the exploration of alternatives, better, safer, cheaper ways to do things, and the development of cleaner products and technologies. Some technologies and developments may be brought onto the marketplace more slowly. Others may be phased out.

Those proposing potentially harmful activities would have to demonstrate their safety andnecessity up front. On the other hand, there will be many incentives to create new technologies that will make it unnecessary to produce and use harmful substances and processes. With the right signals, we will be able to innovate to create development that takes less of a toll on our health and environment.

Q: Naturally occurring substances and disasters harm many more people than do industrial activities.

A: We must deal with the hazards for which we are responsible and over which we have control. Those creating risk and benefiting from their activities also have an obligation not to cause harm. But an important reason for precaution is that we do not yet know, and may never know, the full extent of the harm caused by human activity. Some violent natural events, for example, may be a result of global warming, which in turn is linked to human activity.

Q: We comply with regulations. We are already practicing precaution.

In some cases, to some extent, precaution is already being exercised. But we do not have laws covering each possible industrial hazard or chemical. Also, most environmental regulations, such as the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, and the Superfund law, are aimed at controlling the amount of pollution released into the environment and cleaning up once contamination has occurred. They regulate toxic substances as they are emitted rather than limiting their use and production in the first place. Most current regulations are based on the assumption that humans and ecosystems can absorb a certain amount of contamination without being harmed. There is extreme uncertainty about "safe" or "acceptable" levels, and we are now learning that in many cases we cannot identify those levels.

Q: You can't prove anything is safe.

A: It is possible to demonstrate that there are safer alternatives to an activity.

Q: You could say that every activity has some impact. Every chemical is toxic at some dose.

A: Almost all human/industrial activities will have some impact on ecosystems. The virtue of the precautionary principle is to continuously try to reduce our impacts rather than trying to identify a level of impact that is safe or acceptable.

It is pretty clear from the highlighted sections that there are numerous problems associated with this principle.

|